Kill Bill: Vol. 1

- Lauren Mattice

- Jul 3, 2021

- 3 min read

Updated: Jul 6, 2021

Quentin Tarantino, 2003

When Beatrix Kiddo (Uma Thurman) enters the House of Blue Leaves, go-go music and extraordinary bloodshed reminiscent of Seijun Suzuki’s Tokyo Drifter are not the first references to Japanese cinema that drives the heart and soul of Kill Bill. Through costume, natural fixtures, and music, the Bride’s mission is qualified by the aesthetics of honor and capitulation.

Beatrix’s target is O-Ren Ishii, former member of the Deadly Viper Assassination Squad and head of the yakuza after a swift leap to authority. O-Ren’s protection from Beatrix comes in video game sequences, starting with the clamoring of O-Ren’s assistant Sofie Fatale, who loses her arm to Beatrix’s newly crafted Hattori Hanzō sword.

Over the course of the next forty or so minutes to the tune of “Woo Hoo” by The 5.6.7.8s, Beatrix alerts the restaurant to her presence and O-Ren to their “unfinished business.” In this battle, respect plays its most prominent role—a final countdown to a worthy opponent.

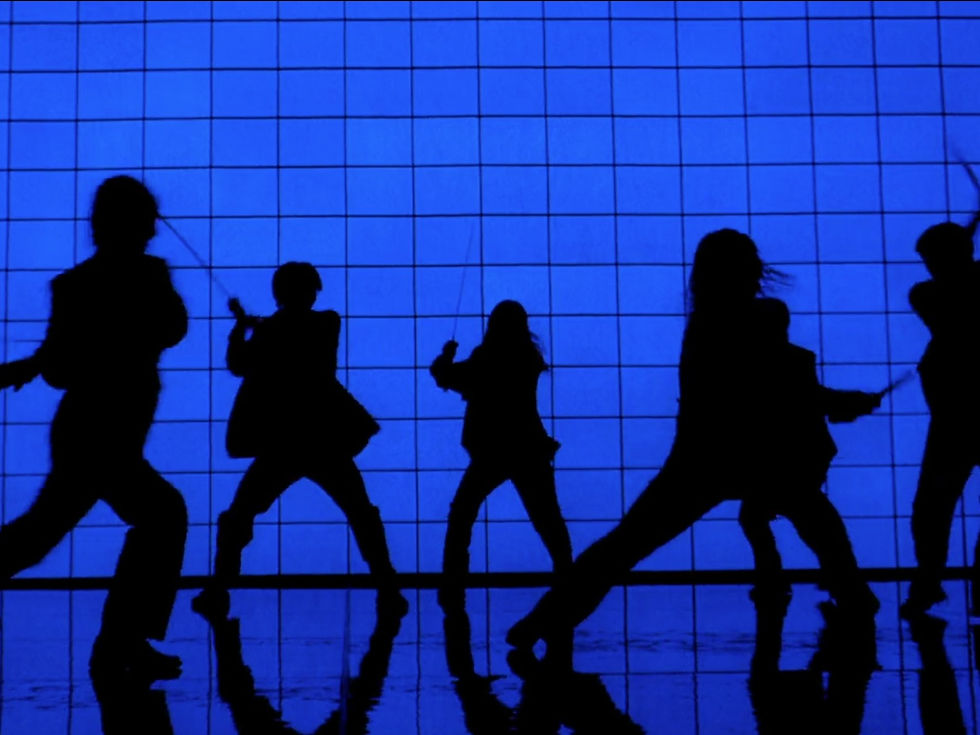

Much like the rest of her opponents, the Bride skillfully sentences both the yakuza Crazy 88 death squad and schoolgirl-gone-psychopath Gogo Yubari to death with a swing of her blade. Both angled medium shots and a blue silhouette frame pay homage to the genre of tokusatsu; the film uses heavy special effects and blood spurting like fire hoses to illustrate the ruthlessness of Beatrix’s rage. A wide shot from the upper balcony of the restaurant captures the carnage: a dance floor made permanently (and a bit humorously) bloody from gaping wounds, and not a square foot of floor without a dead body.

O-Ren is not moved by the outcome. Instead, she waits for Beatrix in the garden, a drastic change in venue with delicate white snow falling and the pitter-patter of a small pond. The Bride, whose yellow tracksuit is distinctly ruined by the bloodshed, bears presence to O-Ren in a simple white kimono. The white not only juxtaposes Beatrix, but serves as a reminder of O-Ren’s past, and the innocence that was taken before she became an assassin; a nod to her livelihood. The latter questions the authenticity of Beatrix’s sword, both sharing the knowledge that its existence was only brought about with the breaking of an oath.

“I hope you saved your energy,” O-Ren quips before Santa Esmeralda’s cover of “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood” begins their duel. O-Ren moves toward her in slow, calculated steps; nothing of the same urgency or disregard displayed in Beatrix’s encounters with Vernita Green and Elle Driver.

The performance is not about revenge: to date, O-Ren is Beatrix’s most formidable foe, and while drawing on Japanese cinema influences, Quentin Tarantino levels the power dynamic with the inclusion of Bushido, or samurai code. With strictures varying from region to region in ancient Japan, respect and honor above all defined the ethics of a righteous warrior and their opponent.

“You might not be able to fight like a samurai, but at least you can die like a samurai.” At O-Ren’s words, with a life-threatening wound on her back, Beatrix challenges in Japanese: “Attack me with everything you have.” When the tides of the fight turn to Beatrix’s favor, and with O-Ren’s kimono stained with blood, the latter apologizes for ridiculing the Bride, to which Beatrix accepts. In shots back and forth, with only their profiles in sight, Beatrix does not go on the attack until O-Ren responds to her teary “Ready?” O-Ren, similar to a samurai accepting their fate, steps closer to death without a fight.

Within seconds, the fight is over and the top of O-Ren’s head is sliced off. “The Flower of Carnage,” sung by Meiko Kaji, brings the battle and Kill Bill’s cinematic influences to a head: the song is the theme of Toshiya Fujita’s thriller Lady Snowblood, a tale of a young woman hunting down the assailants responsible for her family’s murders. Literal and figurative, the tribute commemorates both the will of Beatrix’s mission and the strength and dignity of her opponent, O-Ren.

Comments